How does Pharmaceutical IP work?

Strong intellectual property (IP) protection is a critical pre-requisite for innovation to thrive. The EU has developed a world-class IP regime for medicines: how does it work and why is it so important?

In the pharmaceutical sector, intellectual property (IP) rights, such as patents and regulatory data exclusivity, encourage and protect innovation and provide the needed incentives that drive R&D investments to areas of unmet medical need. An effective IP system gives innovators increased legal certainty that if a medicine makes it to the market, it will be protected from unfair competition for a limited time.

This enables Pfizer and other companies to invest in the long, complex and risky process of discovering, developing, and delivering new medicines to patients, to healthcare systems and to society. It also paves the way for low-cost generics to be used by patients and healthcare systems.

The EU’s IP incentives framework for pharmaceuticals includes:

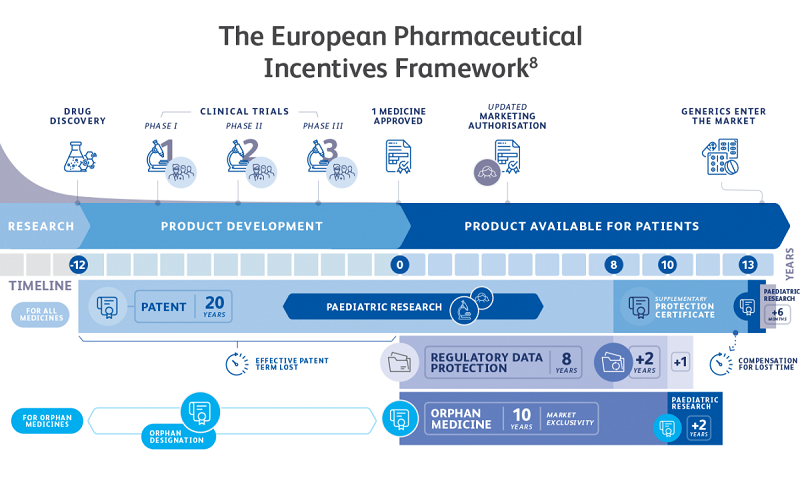

Patents: Patents are provided by national law in all EU Member States. These enable innovators to prevent third parties from using their invention for a period of 20 years1. Patents benefit society more broadly by being published, i.e. they contribute to the dissemination of scientific and technical knowledge, thus helping accelerate follow-on innovation.

Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs): Due to lengthy development and regulatory timelines to obtain marketing authorisation, many new medicines reach the market with just a few years of patent life remaining, not nearly enough time to enable innovators to recover their R&D costs and fund continued innovation. Therefore, EU legislators introduced SPCs which can add a maximum of five years to a pharmaceutical product’s patent-based exclusivity, to partially offset this lost time.

Regulatory Data Protection (RDP): In the EU, RDP provides innovator companies with a protection period of eight years, during which the extensive test data generated by the innovator to support regulatory approval cannot be relied upon by a generic competitor for its own approval process. This is followed by a period of two years during which the generic medicine cannot be placed on the market. RDP starts at the first marketing authorisation of the original (reference) product in the EU/EEA. The protection of RDP is a necessary component of the IP incentives that motivate the continued development of innovative pharmaceuticals.

Investing in medicines for specific populations

Medicines for children: In order to stimulate R&D of medicines for children, the EU Paediatric Medicines Regulation made it mandatory to carry out Paediatric Investigation Plans (PIPs) for all new products (and new indications and forms of existing, SPC protected products), with limited exceptions. As a reward for completing the PIP as agreed with the EMA, and updating the product’s labelling accordingly, the Regulation provides for a one-off six month extension of the product’s SPC (or two years’ extension of market exclusivity for orphan medicines).

Prior to the Regulation, 50% of medicines had not been tested and developed for children. In the past decade, the proportion of paediatric clinical trials has increased by 50% (from 8.25% to 12.4% of all trials conducted in the EU)3.

Orphan Medicines: A rare disease is defined by the EU as any disease which affects fewer than five people in 10,000. There are over 6,000 different rare diseases, and about 30 million European patients affected.4 In order to encourage the development of medicines for rare diseases, the EU Orphan Medicinal Products (OMP) Regulation includes measures such as protocol assistance (i.e. regulatory guidance on development programmes), 10-year market exclusivity from first marketing authorisation, and fee reductions for SMEs.

This figure also shows how much further we have to go in developing treatments for all rare diseases.

Currently the European Commission is carrying out an analysis of pharmaceutical IP incentives, upon Member States’ request6. As a leading global provider of innovative as well as generic and biosimilar medicines, Pfizer supports a robust EU framework for pharmaceutical intellectual property (IP). The current IP incentives ecosystem should be kept competitive and strengthened where unmet medical need persists, e.g. in the fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR), as it provides the foundation for investment in innovation to improve patients’ lives.

Key Policy Points

In the 2019-2024 legislature, we call on the EU and its Member States to:

- Maintain, during the incentives analysis currently under consideration, a world-class IP ecosystem for pharmaceuticals in the EU;

- Consider new incentives to address specific market failures and unmet medical need, for example in the fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR).7

References

1 Patents are granted to eligible inventions that are new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application. The 20 year period begins on the date in which the application is filed.

2 Source: EFPIA, December 2018.

3 European Commission, “State of Paediatric Medicines in the EU”, 2017.

4 EURORDIS, “About Rare Diseases” section.

5 Pugatch Consilium, “Benchmarking Success: Evaluating the Orphan Regulation and its impact on patients and rare disease R&D in the European Union”, 2019 (link).

6 Council conclusions on strengthening the balance in the pharmaceutical systems in the EU and its Member States, June 2016.

7 For more information, read the accompanying paper on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), also available on www.pfizereupolicy.eu

8 Source: EFPIA internal material